On September 14, 2025, a malicious mining pool successfully performed an 18-block “blockchain reorganization” of the Monero blockchain. Qubic, the mining pool, used its mining hashpower to generate an alternative blockchain history and replaced about 70 minutes of the honest chain’s most recent history.

The main effect of the reorganization (“reorg” for short) was the invalidation of 115 transactions that had been included in the original honest chain. The coins in the transactions that were invalidated did not disappear. It is simply as if the transactions never occurred at all. The coins sent by the invalidated transactions returned to the sender’s wallet and it is as if the recipients' wallets never received the coins.

Monero’s protocol requires that users wait for 10 blocks before spending coins that they have just received. Since blocks are produced at a rate of one every 2 minutes on average, that’s a 20 minute wait, on average. The wait is an annoyance for users, but it serves an important purpose.

In normal circumstances, Monero’s “10-block lock” prevents transaction invalidation, but in this extreme case of an 18-block reorg, the 10-block lock was overwhelmed and did not prevent the 115 transactions from being invalidated. In this post, we will see how the much-hated, but misunderstood, 10-block lock on spending newly-received Monero coins can prevent transaction invalidation on short reorgs and how things go wrong when the reorgs are deeper.

We will say that a transaction is “valid” if it has been included in a block on the main blockchain or it is eligible to be mined into a new block on the blockchain. A transaction is “invalid” if it cannot be mined into a new block.

We will compare the validity rules for bitcoin transactions and Monero transactions. Monero transactions need to obey the same basic rules as bitcoin transactions, but with some twists that make Monero special.

How bitcoin does it

A fundamental concept of many cryptocurrencies, including bitcoin and Monero, are transaction outputs. An output is a quantity of the currency inside of a transaction that is spendable. To provide a refresher on the concept of a bitcoin transaction output, I will quote my earlier article analyzing the Bitcoin Cash hard fork:

An output is a concept closely related to – but distinct from – address. An output is identified by its transaction ID plus its position in the transaction outputs, i.e. first position, second position, third position, etc. Once an output is spent by another transaction, it is spent permanently and cannot be reused. However, an address can be re-used repeatedly.

Transactions usually have more than one output because even a payment to a single recipient usually does not use up all of the output being spent. The remaining value, “change” like metal coins returned to a customer in a brick-and-mortar store, is sent back to the sender’s address in a second output in the same transaction.

A new bitcoin transaction that is eligible for inclusion in a new block will contain the transaction ID and the output position (first, second, third, or…) of the output being spent. The output position is the local output index. The index only refers to the position inside of its own transaction. This will be different from how Monero does it.

In bitcoin and Monero, a single blockchain is a consistent version of history. Transactions must appear on the blockchain in the correct order or else users could spend the same coins multiple times or create coins out of thin air.

In a single bitcoin blockchain (i.e. single version of history) a valid transaction must obey these rules that are relevant to our analysis:

- An output that has already been spent cannot be spent again.

- A transaction can only spend an output that has already been included in a prior block or in the same block as the transaction. Spending outputs from thin air is not allowed.

- The spender must prove that they are authorized to spend the output by producing a cryptographic signature with their private key that matches the public key associated with the output.

The only exception to rule #2 is when miners are paid in completely new coins as payment for their service of mining new blocks.

A cryptographic signature is the result of a specific mathematical operation that combines the user’s private key (which is never shared publicly) and the message that authorizes spending.

How Monero does it

Monero has many privacy features. One of them is “ring signatures”. In bitcoin, every signature spends a single output. There is a one-to-one relationship between the output being spent and the transaction that spends it. There is no ambiguity about which output is spent, so the flow of funds is easily traced.

In Monero, a ring signature declares that any one of several outputs are being spent in a given transaction. An external observer cannot know which of the outputs in the ring is actually being spent. Monero’s current ring size is 16, which means that there is one “real spend” hidden in the ring with 15 “decoy” outputs.

How does Monero fulfill the conditions that bitcoin requires of its transactions?

Bitcoin’s rule #1 was “An output that has already been spent cannot be spent again.” Monero makes sure that an output is only spent once by requiring that transactions include the key image of the output that is being spent. Each output has a unique key image that cannot be faked, yet in normal circumstances an observer cannot know which specific output is spent in a ring signature. Once a key image inside a transaction is included in a block, no other transactions with that key image are allowed inside the blockchain.

Bitcoin’s rule #2 was “A transaction can only spend an output that has already been included in a prior block or in the same block as the transaction.” Monero’s rule is similar, with an important difference: Monero transactions can only spend an output that has already been included in a block at least 10 blocks ago. This rule is known as the “10-block lock”. Since decoys and real spends are treated the same in the transaction validation process, all 15 of the decoy ring members must also follow this rule.

Bitcoin’s rule #3 was “The spender must prove that they are authorized to spend the output by producing a cryptographic signature with their private key that matches the public key associated with the output.” In bitcoin, there is a single public key. In Monero at current ring size, there are 16 public keys for every output that is to be spent. For a specified set of 16 public keys, the ring’s cryptographic signature must match the whole set and only that set. You cannot split the signature and somehow replace one or more ring members. If you want to change any of the ring members, you must create a whole new signature, which requires creating a new version of the transaction.

A shortcut

Bitcoin transactions refer to outputs that they spend by their transaction ID and the output index inside that transaction. Monero transactions use a global output index to spend outputs. The global index is a count of every single output that has ever been included in Monero blocks. There are about 140 million outputs on the Monero blockchain already, with more added about every two minutes, on average.

The global output index is a useful shortcut. Ring signatures must refer to many outputs at once. If outputs in rings were referenced explicitly by transaction ID, each Monero transaction would take up much more space to store. A transaction ID requires 32 bytes to store. Integer index numbers take up much less space: 4 bytes or less.

Monero transactions are already much larger than bitcoin transactions. A 2-input/2-output bitcoin transaction is about 0.4 kilobytes. A 2-input/2-output Monero transaction is about 2.2 kilobytes. An unpruned Monero node already takes up about 240 gigabytes of storage for the whole blockchain. Including every single transaction ID explicitly in each ring would increase the size of a 2-in/2-out Monero transaction by about 50 percent. Instead, rings refer to outputs implicitly by their global index number.

Since bitcoin transactions refer to their parent transactions explicitly by their transaction ID, the transactions' validity is basically independent of the exact position of the parent transactions in the blockchain. The parent transaction could be included in the previous block, a block from a week ago, or even the same block that the child transaction is included in. The situation is different with Monero transactions. Since the index of outputs depends on its exact position on the blockchain, the child transaction will not be valid if the index ordering is different from what the child transaction expected.

How can the output index ordering be different from what a Monero transaction was “expecting”?

The 10-block lock establishes the expectation. The global output index in blocks produced 10 or more blocks in the past is not supposed to change. The output index in blocks shallower than 10 blocks can change without major problems.

Such events occur occasionally just as a result of the random mining process. There is no coordination between miners where they “take turns” mining blocks. Each block production is a random event and sometimes random events can occur nearly simultaneously, in different parts of the network. It takes time for new blocks to spread throughout the network. Therefore, short alternative chains can develop occasionally until the whole network agrees on the one longest chain. The short chains that lose the race are eventually ignored by nodes in a process called orphaning. In normal circumstances, honest miners do not try to produce these alternative chains, yet unintentionally a few alternative chains of 1, 2, and very rarely 3 blocks long are produced. The output indices in these alternative chains can differ from each other. However, the short chains do not violate the expectations of new transactions because they are shorter than 10 blocks.

A simplified example

When orphaned chains are 10 blocks or longer, the expectations of new transactions are violated. Therefore, the transactions can be invalidated. Let’s visually walk through an example.

To allow a compact diagram, in this example we will set the ring size to 3 and the block lock to 3. Each transaction will have a single transaction output and each block will have exactly 2 transactions. Coinbase transactions, which are reward payments to miners, are ignored.

The diagram shows the abbreviated transaction output public keys of each transaction. The output index is shown to the right of each public key.

Our transaction is labeled 4b20 and colored purple. Simplifying more, we will treat this 4b20 identifier as if it refers to the ring, output, and transaction itself in one concise label. Our transaction only selects ring members outside of the 3-block lock. When there is a 3-block lock, that means that rings cannot contain outputs from the most recent 2 blocks previous to one that included the transaction. The lock is represented by the red-orange coloring of blocks preceding the block where our transaction was originally confirmed.

The wallet software has created the ring and generated a valid signature for the public keys associated with the outputs in the ring. The ring members have indices 54, 49, and 48. The real spend is output public key f382, with index 49. At this point, no external observer knows that the real spend is f382. The other two outputs in the ring were selected randomly by the wallet software when the transaction was created.

This is the normal functioning of the example chain. New transactions are created. Their rings include outputs from blocks prior to the locked blocks. The transactions, with valid ring signatures, are included in new blocks and all is well.

However, it is possible for a powerful malicious miner to upset the orderly functioning of the blockchain. Even with a minority of total network hashpower, the malicious miner can occasionally get lucky and produce long alternative chains, in secret, faster than the honest miners can produce them. When the malicious miner successfully mines an alternative chain longer than the honest chain, it reveals the chain to the network. Suddenly, nodes in the Monero network realize that the longest chain is the new malicious one and they orphan the honest chain. This event is depicted in the diagram below.

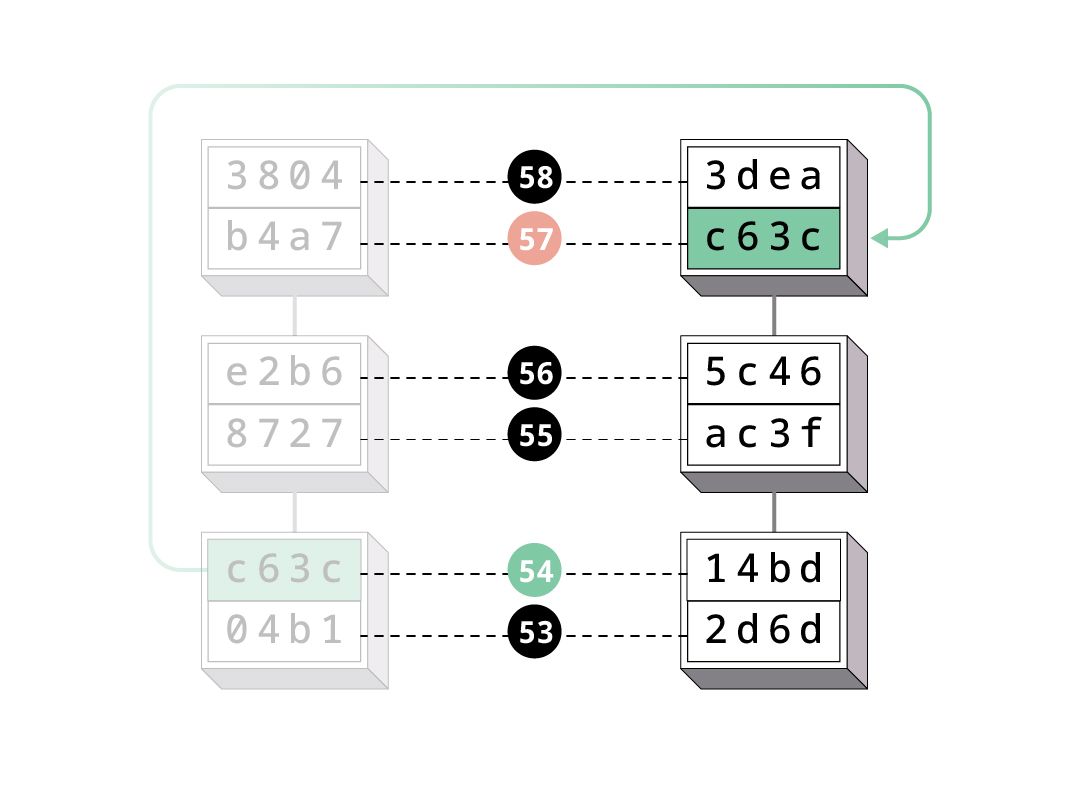

The transactions of the orphaned honest chain are expelled from the orphaned blocks. They are seeking to be included in the new chain, if they have not already been included. Notice that the index numbers on the attacking chain refer to different output public keys than the original honest chain because some outputs are different and the outputs that are the same are in a different order.

Output c63c was originally in the ring created by our transaction. The ring referred to it by index 54. Output c63c is still valid on the attacking chain and actually was included in a later block on the attacking chain. The figure below shows where it went on the attacking chain. It now has index 57 on the attacking chain.

The new output index being out of order is a big problem for our transaction. In the new version of the chain created by the malicious miner, index 54 points to output public key 14bd instead of c63c.

The transaction’s signature for the ring is no longer valid in the new chain history because the whole set of public keys do not match the signature, even though c63c is in the new chain. For our transaction to be valid, the attacking chain must have the exact same transactions in the exact same order as the honest chain, which did not happen here. Our transaction cannot be included in a new block because it is invalid.

Privacy impact

The transaction we created is invalid, but we can create another one that spends the same amount of coins to the same recipient. We change the ring and produce a new signature for that ring. We must include the same real spend, and here is where the ring privacy protections go wrong in this situation. The decoys, randomly selected, are different, but the real spend is the same. The figure below shows the old invalid ring on the left and the new valid ring on the right. The two rings only overlap on one output: f382 at index 49.

Any external observer of the blockchain can see this overlap of the two rings and deduce that the real spend was f382, defeating the privacy protections that ring signatures are supposed to provide. The observer knows that the two rings were trying to spend the same output because the ring has the same key image, as was mentioned before. The figure below summarizes the privacy impact. f382, in yellow, appears in both rings.

18-block reorg

On September 14, 2025, the Monero blockchain experienced an 18-block reorg. The deep reorg violated the assumption that reorg depths would not exceed 9 blocks. The incident invalidated 115 transactions that expected the 10-block lock rule to not be broken.

The 18-block reorg was achieved by Qubic, another cryptocurrency project. For months, Qubic has held a large, yet minority, share of Monero hashpower and has executed short blockchain reorgs to unfairly raise its share of mining revenue through a selfish mining strategy. A clickable visualization of the 18-block reorg event is viewable here.

Does the 18-block reorg mean that Qubic held a majority of hashpower? Not necessarily. Mining is a random process subject to luck. Qubic has had many chances to get lucky. According to block timestamps, Qubic mined a total of 20 blocks in 66 minutes. Assume that network mining difficulty was equal to network hashpower. If Qubic had 40 percent of network hashpower, it would have a 5 percent chance of creating 20 blocks in 66 minutes or less. This result is based on using an Erlang distribution where the shape parameter is 20 and the rate parameter is 0.4 * 1/2, i.e. 40% of the hashpower necessary to produce the usual one block per 2 minutes. Given that Qubic could try again and again, a 5 percent chance per attempt can turn into a very high chance with repeated attempts.

What happened to transactions in the orphaned chain? Most of the transactions (456) were expelled from the orphaned chain and included later in the attacking chain. 115 of the transactions were invalidated because they referenced outputs on the orphaned chain. Below is a table counting the number of transactions invalidated on each block of the orphaned chain. Notice that the first orphaned block at height 3,499,659 contained zero transactions, so no subsequent transactions would have included any outputs from that block inside their rings.

| Orphan chain block height | Valid | Invalidated |

|---|---|---|

| 3,499,659 | 0 | 0 |

| 3,499,660 | 96 | 0 |

| 3,499,661 | 38 | 0 |

| 3,499,662 | 22 | 0 |

| 3,499,663 | 8 | 0 |

| 3,499,664 | 3 | 0 |

| 3,499,665 | 0 | 0 |

| 3,499,666 | 24 | 0 |

| 3,499,667 | 20 | 0 |

| 3,499,668 | 14 | 0 |

| 3,499,669 | 79 | 0 |

| 3,499,670 | 24 | 10 |

| 3,499,671 | 38 | 28 |

| 3,499,672 | 39 | 25 |

| 3,499,673 | 0 | 0 |

| 3,499,674 | 3 | 0 |

| 3,499,675 | 27 | 31 |

| 3,499,676 | 21 | 21 |

Even in the final block of the orphaned chain at height 3,499,676, only half of transactions were invalidated because, by chance, about half of transactions contained no rings that referenced an output in the orphaned chain. Their ring members were all on the chain prior to the first orphaned block at height 3,499,659.

Case study of one transaction

We will follow the journey of one transaction that became invalidated: tx id d3e574c05b01f5d74815e3894f55e1645f402cdbf0415877f49e752a71b0d376.

This transaction was originally included in the orphaned chain at block height 3,499,672. Its ring specified global output index 139,283,631, plus 15 other indices from earlier in the chain. Within the orphaned chain, index 139,283,631 pointed to the output with public key b2de1e442b60b70ac681e9044581bb2dcbf66c97865b340d9a8ae4e3bb8e3d61 at block height 3,499,660. Note that some Monero block explorers label the output public key as a “stealth address”.

However, when the 18-block reorg occurred, the transaction was expelled from the orphaned chain and started to wait to be included in a later block. In the new chain, index 139,283,631 pointed to the output with public key 61b08cd8a250fd2558cdd1a63ebfa38aeea0c9d4395c9223d315439fbc2e0e68 at block height 3,499,665. Since this was a different public key than the original signature was valid for, the transaction cannot be included in a block in the new chain because the old signature is invalid.

About 36 hours later, a new transaction appeared, 2b02f010b63b7a931eaafc681a1c2d2344ef44bdd0998c4b730663b041b4099c. We know that this transaction is related to the original one because its ring has the same key image: 1792997a43d27bb473605424ff3f1f1e1e69b44fec1ebc59dadba713a22eafa8.

The ring members of this transaction are all different except for one, at index 139,282,277. Both the old and new transactions contained this index. This index points to output public key 75254fa644c59a40eed60ad9bc6d9727a152323ac04069de764b72f9fcf3bd6b in transaction eb4f9e77a031c24fad0bb2abab76302e34e200bd3dff52a9f203fc187e2a4ff8 inside block at height 3,499,628, just a few hours before the 18-block reorg occurred. By process of elimination, this output must be the real spend. The ring signature’s privacy protection was defeated.

Double spends and respends

Arguably the greatest negative impact of a deep blockchain reorg is the potential for a “double-spend” attack. In a double-spend attack, a malicious miner uses its hashpower to create an alternative history of the blockchain, then substitutes its history for the honest history. The miner spends the coins to a victim in the honest history, then spends the coins to itself in the attacking chain. Satoshi Nakomoto, creator of bitcoin, described the attack in his 2008 white paper that described the bitcoin protocol:

We consider the scenario of an attacker trying to generate an alternate chain faster than the honest chain. Even if this is accomplished, it does not throw the system open to arbitrary changes, such as creating value out of thin air or taking money that never belonged to the attacker. Nodes are not going to accept an invalid transaction as payment, and honest nodes will never accept a block containing them. An attacker can only try to change one of his own transactions to take back money he recently spent.

To execute the double-spend attack, a miner would have to send Monero coins to a victim, such as a merchant or centralized exchange. The victim would wait a certain number of block confirmations, depending on the victim’s preference, and then send an irretrievable item to the miner, such as a physical good shipped in the mail or coins of another type of cryptocurrency.

Meanwhile, the miner would be mining an alternative chain in secret that contains a transaction that contradicts the “payment” to the victim. Once the malicious miner’s chain was long enough and enough blocks on the honest public chain are confirmed, the miner would broadcast the secret chain, which causes a reorg and reverses the payment to the victim.

A successful double-spend requires the intended victim to take some action, such as sending the perpetrator some item of value. Without the intended victim taking action, the attack has no effect.

In the intentional double-spend attack on the bitcoin blockchain, the perpetrator invalidates the first transaction on the honest chain by mining a contradictory transaction on its secret chain. Bitcoin rule #1, “An output that has already been spent cannot be spent again,” is the violation that invalidates the transaction. In bitcoin, only the original sender of the transaction can invalidate the transaction because only the original sender can sign a transaction that contradicts the first transaction.

As explained previously, a Monero transaction can become invalidated by a deep reorg even if the original sender did not deliberately attempt a double-spend by producing a contradictory transaction. Qubic invalidated the 115 transactions as a sort of collateral damage of its behavior.

Another difference in Monero, compared to bitcoin, is that it is easy to see if two bitcoin transactions sent the same exact amount of coins to the same address, because of its lack of privacy features. In Monero, addresses are hidden on the blockchain through its stealth address feature and amounts are also hidden with confidential transactions technology. Therefore, it is unknown if the later valid transactions just sent the same coins to the same recipient as the invalidated transactions were trying to send in the first place.

As of release of this post (September 26, 2025), about 74 percent of the 115 invalidated transactions had at least one of its ring’s key image confirmed in another transaction after the original transaction had been invalidated. It is maybe better to call these transactions “respends” instead of double-spends because they could have been spent to the original intended recipient. Note that invalidated transactions could have been users sending funds to themselves or users could have completed the original payment to another recipient using a different set of coins or a different wallet. No merchant has yet claimed publicly to be an accidental or deliberate victim of a double-spend as a result of the 18-block reorg.

FCMP transaction invalidation

Full-Chain Membership Proofs (FCMP) is an upcoming upgrade to Monero’s privacy features. Instead of having a small “ring size” of 16, FCMP will, in effect, produce a ring that includes all of the hundreds of millions of outputs ever produced on the Monero blockchain. It is a huge improvement in privacy. How would FCMP transactions handle a deep blockchain reorg?

In one way FCMP perform sbetter than ring signatures, but in another way it performs worse. The privacy impact would be eliminated. Since FCMP transactions would include the whole set of previous outputs in their “rings”, an observer could not perform the process-of-elimination analysis that defeated the privacy of small rings when transactions are invalidated and need to be reconstructed.

However, since current-version Monero rings only select a limited number of outputs from the reorg zone, there is only a chance, not a guarantee, that the transactions outside of the 10-block lock are invalidated. In the actual 18-block reorg, only about half of transactions that could have been invalidated actually were, because of luck of the ring signature draw. If they were FCMP transactions, all transactions above the 10-block lock would have been invalidated because all of them would reference all transactions from 10 blocks and earlier.

anhdres created all diagrams in this post.

Special thanks to DataHoarder for extracting and hosting extended data about the reorg incident here and here.

jeffro256 and DataHoarder reviewed an earlier version of this post and provided feedback.

Open source code used to produce of the empirical analysis in this post is here.

If you enjoyed this article, consider supporting my work with a donation of XMR, BCH, BTC, or WOW.